C-7 Home Page

Distribution

![]() Products

& Services

Products

& Services ![]() Product Lines

Product Lines ![]() Order

Order ![]() Consignment

Consignment ![]() Library

Library ![]() Search C7.com

Search C7.com

![]()

![]()

![]() Notes & Interesting Articles

Notes & Interesting Articles ![]() Pricing

Pricing ![]()

![]()

![]() Special Optics

Special Optics

Nikon Special Products Overview

Specialized limited availability Nikon products offered by Company SevenThe Nikon Corporation is foremost a technology company. The history of this company is well documented at numerous other sites and so this article will not dwell on their numerous accomplishments and innovations beyond those examples mentioned below. To this day Nikon operates as a series of companies known as the 'Nikon Group', with many new companies assimilated or started over the recent decades and with each dedicated to a particular field of expertise but that can be called upon by each other to devise new solutions and technologies. Nikon is a core member of the Mitsubishi Group of Companies, a Japanese conglomerate. Nikon remains prominent and relevant in many areas of manufacturing including binoculars, spotting telescopes, microscopes, measurement instruments, and the steppers used in the photolithography steps of semiconductor fabrication. But to most American consumers Nikon represents one of the two major names in film and digital camera and lens technology.

It is important to know this is a company whose corporate culture historically stressed innovation with a balance of modern mass production techniques, interchangeability of components, and good quality control. As can be seen by just some of the innovative lenses mentioned below, in many of these instances too few lenses of each type were made to justify the effort because there was more to their corporate identity than profit alone.

History But one should know the history of Nikon began well before 25 July 1917 when three leading optical manufacturers in Japan merged to form one more comprehensive and better integrated optical company known as Nippon Kōgaku Kōgyō Kabushikigaisha (日本光学工業株式会社 “Japan Optical Industries Corporation”). The company became known in many areas including the production of optical and measuring equipment, binoculars, small telescopes and even larger and more complicated astronomical telescopes. In 1921, Nikon released its MIKRON compact binocular that was so well regarded that in 1997 an optically updated version of the same basic design was reintroduced as the 6x15M CF model. In 1922 Nippon Kōgaku had completed their largest to date, a 20-inch (50 cm) reflecting telescope. In 1925 they introduced microscopes marketed under the JOICO ("Japan Optical Industries Co") trademark. JOICO is a trademark made up of the initial letters of the Japan Optical Industry Co., which is a literal translation of Nippon Kogaku K.K. the company's name at the time.

History But one should know the history of Nikon began well before 25 July 1917 when three leading optical manufacturers in Japan merged to form one more comprehensive and better integrated optical company known as Nippon Kōgaku Kōgyō Kabushikigaisha (日本光学工業株式会社 “Japan Optical Industries Corporation”). The company became known in many areas including the production of optical and measuring equipment, binoculars, small telescopes and even larger and more complicated astronomical telescopes. In 1921, Nikon released its MIKRON compact binocular that was so well regarded that in 1997 an optically updated version of the same basic design was reintroduced as the 6x15M CF model. In 1922 Nippon Kōgaku had completed their largest to date, a 20-inch (50 cm) reflecting telescope. In 1925 they introduced microscopes marketed under the JOICO ("Japan Optical Industries Co") trademark. JOICO is a trademark made up of the initial letters of the Japan Optical Industry Co., which is a literal translation of Nippon Kogaku K.K. the company's name at the time.

Right: Nippon Kōgaku Kōgyō Kabushikigaisha (Nippon Kōgaku Tōkyō K.K.) company logo used from 1917 to 1946 (5,864 bytes).

Moving into the 1920's Nikon worked to produce more sophisticated camera lenses but the company lacking engineering know-how ran into roadblocks. By 1921 Nippon Kogaku persuaded eight German optical engineers to come to work for the company. These men including Heinrich Acht were instrumental in helping to get Nippon Kogaku onto the right track. A series of lenses whose designs were modeled on the Zeiss Tessor were designated "Anytar" lenses. The German engineers returned home in 1928 as in turn Kakuya Sunayama, the General Manager of the Lens Design Department, visited Germany to learn more about optics. Mr. Sunayama acquired a Carl Zeiss 50cm F4.8 Triplet (three element) lens. The Zeiss lens would be taken apart, studied, and essentially copied so that by 1929 Nippon Kogaku had completed their first prototype camera lens the Tessor-type Anytar 50cm F4.5. This was followed by the Anytar 12cm F4.5 at the end of 1929, as well as the 7.5cm and 18cm focal length lenses. By 1930 the Triplet, the Tessor and the Dagor type lenses were in production. Improving upon the original designs by 1931 the Anytar 12cm F4.5 was said to have become competitive wit the Zeiss Tessor. With the prospects for developing a system of photographic lenses it was decided to market them under a unifying name, thus the NIKKOR brand was born in 1932.

The company geared up for military production as the demands of Imperial Japan escalated throughout the 1930's and through 1945. The NIKKOR lenses used for aerial photography were designated "Aero-NIKKOR." The first orders for the Aero-Nikkor lenses came in 1933 from the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force, these were for the 70cm F5 and the 18cm F4.5 NIKKOR lens for small-scale aerial photography. The company expanded to some nineteen facilities employing 23,000 people.

Even during the war the company was involved in making instruments for science, even being asked in 1942 to construct an objective lens for the Tokyo Astronomical Observatory (TAO) coronagraph; this project was not completed then. By 1946 the company was gradually returning to the manufacture of consumer items including cameras and to distinguish it at this new start, the 'Nikon' logo was adopted. The TAO was renamed National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, and in 1947 promptly resurrected the coronagraph project that was completed in 1949 and opened at Norikura in March 1950. This was only the sixth instrument of its kind in the world, and owing to its longitude complemented those systems in Europe and in the United States. In 1971 a Nikon 25 cm Coudé-type coronagraph was completed and installed in a dome at the same Norikura facility - at the time this was the third largest instrument of its kind in the world. The Norikura facility remained in operation until March 2010 when the Japanese Earth orbiting satellite Hinode took over the work - we think "just wait 'till the next Solar Maximum fries the satellites - they'll be begging to open Norikura!"

![]() In October 1945 the company Board of Directors decided to focus their main efforts on the development of photographic camera and lenses for the consumer market; this was considered critical to the survival of the company in post-war Japan. By 1946 their 'Camera and Projector Committee' had refined the concept of a "universal-type small-size camera." This resulted in the completion in November 1947 of the first two of some twenty prototype Nikon rangefinder cameras, what would become known as the 'Nikon I' model. The prototype stage was completed by February 1948 and the production models were made available for sale later in 1948. These would go on to complete directly against Zeiss and Leica cameras. Even though this camera put Nikon on the radar so to speak, they would run away with the camera market by adopting and improving an idea developed by the German companies but dismissed out of hand by them: the Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera.

In October 1945 the company Board of Directors decided to focus their main efforts on the development of photographic camera and lenses for the consumer market; this was considered critical to the survival of the company in post-war Japan. By 1946 their 'Camera and Projector Committee' had refined the concept of a "universal-type small-size camera." This resulted in the completion in November 1947 of the first two of some twenty prototype Nikon rangefinder cameras, what would become known as the 'Nikon I' model. The prototype stage was completed by February 1948 and the production models were made available for sale later in 1948. These would go on to complete directly against Zeiss and Leica cameras. Even though this camera put Nikon on the radar so to speak, they would run away with the camera market by adopting and improving an idea developed by the German companies but dismissed out of hand by them: the Single Lens Reflex (SLR) camera.

Above: Nikon logo used since March 1947 (5,864 bytes).

Nikon gradually expanded into many areas of optics from opthalmic lenses to medical diagnostic instruments. By 1947 they had resumed production of measuring instruments. Among many noteworthy achievements of the company on that stands out was the introduction in 1959 of the Nikon F, their first SLR camera. The Nikon F is argued by many to be the most significant 35mm SLR camera development ever, the first true 'system' camera with interchangeable components that could tailor the camera to do many tasks exceptionally well. The Nikon F, which was often used in the titanium curtain experiments, was the first production camera to actually incorporate titanium shutter curtains displacing the less durable cloth shutter curtains used in prior SLR cameras. Many GI's returned from Korea with Nikon cameras. In the 1960's and 1970s the veterans of Vietnam fondly recall their acquisition of the fine Nikon F series cameras in Asian markets at amazingly low prices - back then the Dollar was still worth seventy cents.

In January 1971 Nikon was first commissioned to build 35mm SLR 'space cameras' tailored specifically for the NASA Apollo Program, these were to supplement the special Hasselblad medium format 70mm cameras then in use. This was a prestigious corporate mission, and so a special team at Nippon Kogaku's Ohi Plant was assigned to develop these cameras.

Left: Nikon FTN space camera with 55mm f/1.2 lens (29,325 bytes).

These first space cameras were based upon the Nikon Photomic FTN (built on the F body) but made with modifications to meet NASA specifications. These cameras had to survive the rigors of space flight and be manageable by the astronauts even when wearing gloves. The most obvious distinctions are that instead of natural metal finish and leather covering their exterior is finished in a special matte black paint so that these will not reflect sunlight. The shutter button pad and film advance lever were enlarged, and film counter numbers and the cover window were made larger to be easier to read. The focus dial incorporated two levers to facilitate handling. The finish, lubricating oil, and other materials used in the cameras met special requirements. These camera battery compartment can not leak, nor do these cameras emit radio frequency interference (RFI) that might impact other electrical systems aboard the spaceship. Wire soldering and strain relief met NASA space flight standards. The cameras remain reliable even after exposure to extremes of temperature and humidity, operating in zero gravity and yet able to survive launch and landing induced vibration and impact of up to approximately 7 G's. The Nikon team delivered the first nine of these cameras to NASA in June 1971 - just about six (6) months!

The first of these FTN first flew in July 1971 aboard the Apollo 15 moon landing mission. The F model variants would be followed by generations of Nikon space cameras continuously improving the performance and versatility; these were built the professional F2, F3, F4, F5 and F6, and D3s.

- Nikon 6mm f/2.8 Fisheye - a nearly 11 lb. monster lens with twelve lens components assembled in nine groups introduced to the world at Photokina in 1970. The lens is 10 inches in diameter providing a circular actual field of view 220 degree wide, so this lens can literally see behind itself!

-

between 1969 and 1978 Nikon made just under 200 of these lenses including prototypes.

- Nikon 58mm f/1.2 Noct - in 1977 this became the world's first production SLR lens incorporating an aspheric component to control spherical aberration and coma. Designed by Shimizu Yoshiaki this also corrects the troublesome sagittal coma flare otherwise produced when using such a super fast lens at the maximum aperture - this lens delivers amazing images under all conditions.

-

between 1976 and 1998 Nikon made three versions of the lens amounting to a total of about 11,500 of these lenses, including prototypes.

- Nikon 105mm f/4.5 UV-NIKKOR - the most versatile and high performing multispectral imaging capable refractive SLR lens ever offered.

-

between 1985 and 1999 Nikon sold about 3,030 of these lenses. In November 2006 production resumed averaging about 30 lenses sold per year.

- Nikon 200mm f/2 ED IF - the world's fastest 200mm lens when introduced in April 1977. It was developed by a Nikon team headed by Soichi Nakamura and Kiyoshi Hayashi so that it could be hand held by professional press and sports photographers, particularly when covering gymnastics. Originally marketed as the Ai Nikkor 200 mm f/2S IF-ED, this was an amazing and unprecedented lens design with a then unprecedented 122mm aperture front lens patented on 4 December 1979 as the "Telephoto Lens With Large Relative Aperture".

-

since 1977 Nikon has sold more than 8,500 of these lenses in manual and autofocus configurations. The current model is designated the AF-S 200mm f/2 G IF-ED VR.

- Nikon 300mm f/2 ED IF - the fastest 300mm lens ever made, and not rivaled since. With a 160mm aperture and 52mm drop-in filters, and a matched 1.4x teleconverter (400mm f/2.8) this too delivers amazing images even hand held, and under all conditions. The 300mm f/2 ED IF lens and its cousin the 400mm f/2.8 ED IF lenses are such an amazing accomplishment, that we host an article Nikkor 300mm f/2 ED IF and Tochigi Nikon 300mm T2.2 and feature examples of these in our collection of optics.

-

between 1983 and 1985 Nikon made about 441 of these lenses, with the first ones delivered well in time for the 1984 Olympics.

- Nikon 1200-1700 f/5.6-8 P IF ED - the largest Zoom refractive lens of its time. Weighing in at 35 lbs (16 kg), this 34-1/2 inch long, 9.3 inches wide behemoth is not going to appear at too many casual photo ops.

-

between 1988 and 1998 Nikon sold just about 15 of these lenses

Corporate Identity Decades ago was a time when pride of innovation dictated corporate identity moreso than in the recent years when decisions are often made by bean-counters who may know the price of everything, but the value of nothing. We think back to the 1970's and 1980's when Nikon dominated professional 35mm single lens reflex (SLR) camera and lens technology. This was a time when a corporation like Nikon would put its best minds to work at developing truly amazing lenses in addition to those that simply made good commercial sense.

Corporate Identity Decades ago was a time when pride of innovation dictated corporate identity moreso than in the recent years when decisions are often made by bean-counters who may know the price of everything, but the value of nothing. We think back to the 1970's and 1980's when Nikon dominated professional 35mm single lens reflex (SLR) camera and lens technology. This was a time when a corporation like Nikon would put its best minds to work at developing truly amazing lenses in addition to those that simply made good commercial sense.

Right: Nikon 300mm F/2 ED-IF Lens (SN 182429) the fastest 300mm lens ever in production! Here with Nikon 35mm SLR camera attached as displayed at Company Seven set up for wide sky astrophotography ‘piggybacked’ atop a 102mm refracting guide telescope and German Equatorial mount (41,849 bytes).

Click on image to see enlarged view (288,973 bytes).

Nikon is responsible for many firsts in camera lens history, but just consider some of the more spectacular ones that we’ve known at Company Seven listed here for example:

As one can clearly see Nikon was the camera brand mentioned in song and featured in the hands of most professional during an era where they simply pushed beyond traditional lens making boundaries. Even with the transition to the autofocus and then digital cameras Nikon stayed loyal to their durable "F" style bayonet mount that was introduced in June 1959 on the original "F" camera body. In 2009 Nikon celebrated the 50th anniversary of the F mount - every Nikon camera made through today can accept any Nikon lens made over the decades, and these can be made to work at least manually even if not all features (autofocus, etc.) may be compatible between the lens and camera body.

As one can clearly see Nikon was the camera brand mentioned in song and featured in the hands of most professional during an era where they simply pushed beyond traditional lens making boundaries. Even with the transition to the autofocus and then digital cameras Nikon stayed loyal to their durable "F" style bayonet mount that was introduced in June 1959 on the original "F" camera body. In 2009 Nikon celebrated the 50th anniversary of the F mount - every Nikon camera made through today can accept any Nikon lens made over the decades, and these can be made to work at least manually even if not all features (autofocus, etc.) may be compatible between the lens and camera body.

Tumultuous Decades of Change

From the late 1960's through the mid 1980's Nikon came to dominate the world 35mm SLR camera market. In particular Nikon continued to enjoy the fruits of the growing market in the Americas, all the while expanding into other countries too. Japanese industries as a whole benefitted from the fixed exchange rate of ¥360 per US $1 enacted in 1949 through a United States plan (part of the Bretton Woods System) to stabilize prices of the postwar Japanese economy. This remained in effect though 1971 when the U.S. abandoned the Gold Standard. By the late 1960's this was benefitting Japanese exports as they were very affordable overseas, but the flip side of this is that imported items then cost the average Japanese citizen dearly.

From the late 1960's through the mid 1980's Nikon came to dominate the world 35mm SLR camera market. In particular Nikon continued to enjoy the fruits of the growing market in the Americas, all the while expanding into other countries too. Japanese industries as a whole benefitted from the fixed exchange rate of ¥360 per US $1 enacted in 1949 through a United States plan (part of the Bretton Woods System) to stabilize prices of the postwar Japanese economy. This remained in effect though 1971 when the U.S. abandoned the Gold Standard. By the late 1960's this was benefitting Japanese exports as they were very affordable overseas, but the flip side of this is that imported items then cost the average Japanese citizen dearly.

However, even as early as 1969 there were ominous signs on the horizon. Among these were an increase of tensions regarding competition and trade issues between the USA and Japan. These came to the limelight in 1969 when President Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato met in Washington, DC on November 19, 20 and 21, to discuss world events and matters of mutual interests to the United States and Japan. The meetings included discussions about trade imbalances and trade liberalization - making Japan's markets more accessible for U.S. products; this was not to be the last time these matters would come up so publicly. The discussions closed with an statement where parties agreed to 'try harder' (as usual when U.S. trade representatives meet foreign delegations) to address the large imbalances in trade and payments between the USA and Japan. This in part led to the Smithsonian Agreement, taking effect in 1972 that set the exchange rate of ¥308 per US $1. But this was impossible to maintain given market pressures and so by early 1973 the rates were abandoned and the Yen's exchange rate was allowed to float with the Yen averaging about ¥290 per US $1. But more about this later.

By the mid 1970's it seemed as though any camera store with some measure of credibility was offering at least some of Nikon's cameras if not the professional "F2" series cameras too. Many other SLR makers were in the fray competing for the sales most notably including Canon, Contax (Kyocera), Leica, Mamiya, Minolta, Olympus, Pentax, and Yashica. The worsening condition of the U.S. economy through the 1970's (in part attributable to the costs of the Vietnam war) lead to high U.S. interest rates, while the Yen rose to peak in 1973 at an exchange rate of ¥271 per US $1. By 1980 the exchange rate was ¥227 per US $1. This combined with the energy crises and rising costs during the 1977 to 1981 term of President Jimmy Carter meant there was more and more competition in the USA for fewer sales of the most esoteric lenses. As we have observed again after the financial crises of the 'Wall Street Bailouts', the housing bubble burst of the recent years: most people NEED milk and gasoline, they do not need esoteric cameras.

By 1979 Nikon and other photo companies experimented with ways to make affordable but less sophisticated lenses and cameras. Nikons efforts included the EM camera and in 1980 the 'Series E' lenses were announced. These included fixed focal length lenses: E 28mm f/2.8, E 35mm f/2.5, E 50mm f/1.8, E 100mm f/2.8 E, and E 135mm f/2.8. Three Zoom lenses rounded out the selection: S 36-72mm f/3.5, E 75-150mm f/3.5, and the E 70-210mm f/4. The Series E provided good value in terms of optical performance, production was streamlined to cut manufacturing costs, f ratios and design were moderated to reduce the number of elements and glass costs, and their mechanical components included some plastic parts instead of the traditional more robust metal construction. So these lenses weighed less and cost less than their conventional 'Nikkor' series lenses. The Series E lenses were such a good value given their cost and performance that we wonder if Nikon dropped the line in 1985 owing to the impact these might have had on their conventional Ai-S lenses?

Even with the U.S. economy ailing one could walk into one of at least several professional photography oriented camera stores in any urban area and see an amazing collection of wonderful Nikon lenses and cameras. I recall seeing almost every major Nikon ED IF lens displayed at Ritz Camera headquarters in Beltsville, Maryland. And I could see an impressive selection of the best Nikon cameras and lenses at several other stores too in the Washington, DC region. But by 1980 one could find pages and pages of price based advertisements in the larger photography magazines including Modern Photography and Popular Photography. These ads spaces were dominated by New York City based mail order oriented companies; a number of these were operated by the local religious community and were arguably subsidized at times by sales from their diamond and other industries. Some of these companies demonstrated less than ethical ideals (selling 'gray market' or stolen goods, stripping accessories or ordering systems without those that might be expected to be included, etc.) and it would take years before the worst were ferreted out or changed practices. The increased competition from mail order destroyed some smaller community photography shops, or caused others to discontinue stocking the more esoteric cameras and lenses; why pay to show something to many customers who would ultimately walk out and order the item from New York to save some percentage plus sales tax (then 4% in Maryland)?

Company Seven became a reseller for Nikon sports and photographic gear. But by the mid 1980's we learned how Nikon and the other major cameras manufacturers seemed to kowtow to the mostly mail-order oriented high volume sellers. Then Nikon and most other camera companies based their price lists on a sliding scale where the retailer's best discounts were predicated on ordering in some volume. Company Seven was among many smaller shops that basically had to give up selling Nikon products simply out of embarrassment. We would be called 'expensive' when a customer learned he could buy a Nikon binocular, spotting telescope or camera from New York mail order houses for about the same cost or less than what smaller retailers (including Company Seven) paid to buy direct from Nikon. We sense Nikon did not care that they were destroying almost every small local store, we sensed their sales overall were sliding all while fewer and fewer volume oriented stores sold more of the shrinking pie.

Nikon 6mm Fisheye to 1200-1700mm Zoom and 2000mm Mirror Lenses

By the end of the 1980's Nikon had developed the most amazing and comprehensive line-up of lenses.

However, one could see fewer and fewer of these stocked at camera stores outside of New York City (68,461 bytes).

Click on image to see enlarged view (415,115 bytes).

The decline of Japanese dominance of the U.S. market: As Japan's costs of real estate and living soared with their increasingly improving lifestyles, the costs of Japanese made products increased too. Furthermore, under the administration of President Ronald W. Reagan high spending in some areas combined with various exemptions to planned budget cuts, and the loss of federal revenue from tax cuts, created difficulties in balancing the federal budget. As a result, the government borrowed extensively to pay its bills issuing Bonds and the like so U.S. government debt about tripled from 1980 to 1988. Much of this money came from abroad, especially from Japan. Borrowing money to pay the debt caused the U.S. government to spend a greater proportion of its budget on interest payments for loans. The budget deficit kept interest rates so high that the value of the dollar soared in relation to major foreign currencies. Consumer spending for manufactured products grew, but this was mainly spent for inexpensive imports. As a result the United States further increased its foreign debt throughout the 1980s by spending more on imported goods than it earned from exports. The U.S. trade deficit climbed from $24.2 billion in 1980 to $152.7 billion in 1986. By 1986 with James Baker as Treasury Secretary, an effort began to reduce foreign indebtedness and the U.S. government devalued the dollar. Devaluation, which lowered the value of the dollar in relation to foreign currency, made American products less expensive and therefore more desirable in foreign markets. During the next few years, the dollar declined in value by over 40% on a trade-weighted basis and encouraged a major revival of U.S. exports. However, devaluation failed to erase the trade deficit.

The decline of Japanese dominance of the U.S. market: As Japan's costs of real estate and living soared with their increasingly improving lifestyles, the costs of Japanese made products increased too. Furthermore, under the administration of President Ronald W. Reagan high spending in some areas combined with various exemptions to planned budget cuts, and the loss of federal revenue from tax cuts, created difficulties in balancing the federal budget. As a result, the government borrowed extensively to pay its bills issuing Bonds and the like so U.S. government debt about tripled from 1980 to 1988. Much of this money came from abroad, especially from Japan. Borrowing money to pay the debt caused the U.S. government to spend a greater proportion of its budget on interest payments for loans. The budget deficit kept interest rates so high that the value of the dollar soared in relation to major foreign currencies. Consumer spending for manufactured products grew, but this was mainly spent for inexpensive imports. As a result the United States further increased its foreign debt throughout the 1980s by spending more on imported goods than it earned from exports. The U.S. trade deficit climbed from $24.2 billion in 1980 to $152.7 billion in 1986. By 1986 with James Baker as Treasury Secretary, an effort began to reduce foreign indebtedness and the U.S. government devalued the dollar. Devaluation, which lowered the value of the dollar in relation to foreign currency, made American products less expensive and therefore more desirable in foreign markets. During the next few years, the dollar declined in value by over 40% on a trade-weighted basis and encouraged a major revival of U.S. exports. However, devaluation failed to erase the trade deficit.

We would see the steady decline in U.S. buying power accelerate so that by 1988 the exchange rates were at about 128 Yen per dollar!

This devaluation did have the impact desired at least initially, we in the USA slowed the buying of Japanese products. From an exchange rate of ¥220 per US $1 at the end 1981, then ¥250 per US $1 at the start of 1985, the yen rose to a peak of ¥123 at the end of 1988; the impact of this was that Japanese products virtually doubled in cost to the American consumer. But there were few U.S. companies bringing production back - most manufacturers and even Japanese companies simply looked elsewhere to countries where products could be made for less than Japan. It is interesting to note that we read about Nikon opening facilities in Thailand, Fujinon allying with a maker in China, and other moves away from Japan in part for financial reasons, but we also understood the environmental regulations were less stringent outside Japan too; this cut manufacturing costs - and jobs in Japan.

We at Company Seven observed the price of the highly regarded Japanese made products skyrocket over this period. Between its introduction in 1980 for about $550 the mail order price of the venerable Nikon F3HP camera body had increased to $1,200 in 1995. The professionals and the more demanding members our community at least initially did not suffer much from the cost increases. However, the more economical to advanced range of cameras and lenses suffered in sales. As if the economic news were not bad enough, in the 1990's journalism and media publications showed signs of saturation and pronounced changes as news staffs were consolidated and images were increasingly shared among organizations; this resulted in cutbacks in spending on the more esoteric lenses. After all how many 600mm f/4 lenses does a news organization need?

This is all before the impact of digital media and flight of consumers to free sources of information (the Internet) commenced in about 1994.

Transition from Film to DSLR: the workhorse Nikon F3 camera body and its derivatives were so well regarded by professionals and advanced amateur alike that it remained in demand even as the F4 cameras came available in 1988, and the F5 came along in 1996! From 1997 to 1999 Nikon released some consumer oriented digital cameras, then introduced the 'Coolpix' series of pocket size digital cameras. But those of us who had invested heavily in Nikon lenses awaited some good news from Nikon, all the while our friends touted their latest Canon digital SLR body and lenses (their first DSLRs of note were the EOS DCS 3 introduced in 1995, the Canon EOS D2000 of 1998). As the major camera makers produced more compact and versatile pocket size cameras, ironically this too took its toll on the sales of the formerly lucrative SLR systems and their accessories. While no compact pocket camera can take an image as well as what may be done with an SLR with the nominal lens, and filter, and flash with flash slaves, etc. by the time most people dragged an SLR out and had it set up to take one picture, those who have a Coolpix are likely to have captured the moments with dozens of images. This goes back to the philosophy taught by Company Seven of "the best telescope or optical gear is the one that gets used".

Ilford HP5 Plus Film black & white print emulsion. |

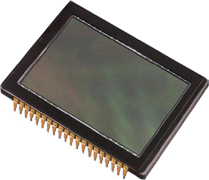

Kodak KAI series Charge Coupled Device (CCD) |

Click on images to see enlarged views (218,292 and 300,006 bytes).

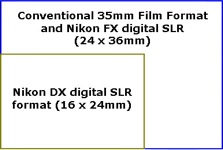

Though imaging Charge Coupled Devices (CCD's) were still improving and not inexpensive, in June 1999 Nikon entered the professional digital SLR camera market with their D1. The Nikon D1 is a 2.7 megapixel camera with the with the 15.7 x 23.7mm sensor (1.52x crop factor) that came to be marketed as the Nikon DX format. All the early production DSLR cameras and most of those sold today incorporate a sensor with a smaller dimensional area than that of a conventional 35mm format (24 x 36mm) film frame. While these smaller sensors do preserve the approximate 3:2 aspect ratio of 35mm film, the smaller formats crop the larger image circle of conventional 35mm SLR lenses reducing the actual field of view to about forty two percent (42 %) or less, depending on the format, of the area that lens will show on a conventional 35mm SLR camera.

Though imaging Charge Coupled Devices (CCD's) were still improving and not inexpensive, in June 1999 Nikon entered the professional digital SLR camera market with their D1. The Nikon D1 is a 2.7 megapixel camera with the with the 15.7 x 23.7mm sensor (1.52x crop factor) that came to be marketed as the Nikon DX format. All the early production DSLR cameras and most of those sold today incorporate a sensor with a smaller dimensional area than that of a conventional 35mm format (24 x 36mm) film frame. While these smaller sensors do preserve the approximate 3:2 aspect ratio of 35mm film, the smaller formats crop the larger image circle of conventional 35mm SLR lenses reducing the actual field of view to about forty two percent (42 %) or less, depending on the format, of the area that lens will show on a conventional 35mm SLR camera.

Right: "What's the big deal?" - the respective areas of Nikon DX (15.5 x 23.3 mm) and FX (35.8 x 23.8 mm) formats compared (13,900 bytes).

Click on image to see enlarged view (92,281 bytes).

The DX format means our expensive 24mm lens provides results like a 37mm lens, our 35mm lens images look as though they were taken by a 54mm lens, our Nikkor-UV 105mm macro lens seems like a 162mm lens, etc. To help avoid confusion among users who were transitioning from film to these smaller format DSLR cameras, Nikon simultaneously introduced a series of lenses scaled to provide coverage commensurate with their represented focal lengths. In our opinion, and especially after considering Canon's offerings, the D1 was too little and too late. By 2002 Canon had introduced the EOS 1Ds with a full frame (35.8 x 23.8 mm) CMOS. In July 2003 the D2H came along with its 4.1 megapixel 1.55x crop factor Nikon DX (15.5 x 23.3 mm) format; for me this was "so what, look at Canon with a full frame DSLR".

If you want to say something nice about the DX format that is these are lighter weight and more compact cameras and lenses than those of the FX format system. As newer DX camera models provide increased megapixel density and their features are improving, and selling for less than the FX cameras, the DX is particularly attractive to the amateur and may continue to be sold for some time to come.

In September 2004 Nikon introduced its first complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) based digital cameras with the D2X providing a finally respectable 12.4 megapixels, though this still has the DX format of about 15.7 x 23.7mm. The D2X remained the flagship of the line until the D2Xs was introduced in June 2006.

In 2004 the Nikon F6 camera was introduced; this is likely to be the last professional film camera of the F series developed by Nikon since the original F was introduced in 1959. The F series evolution tended to show nothing but improvements, but we see the F6 as somewhat of a compromise camera that might reflect Nikon's efforts to cut costs and thereby versatility. There is not the selection of options for the F6 as there were with the F5 and prior F cameras. So the F6 can not be configured to suit as broad a variety of applications. For example, in my years of using these cameras I could interchange the prism viewfinder focusing screen of my F2, F3, F4 and F5 cameras but the F6 does not permit this. There is no Aperture Direct Readout (ADR) feature on the F6, although my prior F cameras have that and so it is a simpler matter to see the aperture setting in the finder. No to be obstinate, but I think of the F5 as the last truly great Nikon F series camera.

In July 2008 Nikon released the D700 and then in August the D3, their first full frame (24 x 36mm) format DSLR cameras. These full frame cameras bear the Nikon 'FX' format designation so we could FINALLY USE ALL our great Nikon lenses (Fisheye, perspective control shift lenses, fast wide angle lenses, etc.) to their full advantage. With the D3 incorporating a 12.1 megapixel CMOS; we sensed Nikon was back into contention for the professional and more demanding amateur markets. By the time Nikon released the 24.5 megapixel D3x in December 2008 we were happy again to be Nikon owners, no longer looking back and missing any aspect of the film cameras even though the price of the D3x (and computers to manage the raw 69.8 MB files) left us financially poorer for it. By October 2009 the D3s was released; we had forgot there ever were film cameras and all was forgiven.

Left: D3s FX format camera with the AF-S NIKKOR 14-24mm f/2.8G ED lens as provided to NASA (23,228 bytes).

In 2008 NASA selected the D2Xs digital SLR along with some thirty five (35) lenses for use at the International Space Station (ISS) to document activities such as inspections and maintenance operations. These were followed into space by the FX format D3 cameras. Extreme credibility came to the Nikon digital SLR's line when in 2009 NASA selected the D3s FX format camera with the AF-S NIKKOR 14-24mm f/2.8G ED lens to join the Nikon D2s cameras, lenses, and Speedlights to photograph activities on the Space Shuttle and at the ISS. Interestingly enough no special modifications were necessary for these D3s cameras to be 'Space Flight Qualified"; they are the same models available to end-users! This confirms the incredible performance, reliability and durability of the Nikon D3s.

Above: Nikon images taken with Nikon digital SLR cameras in space: astronaut EVA (74,337 bytes), apple (67,699 bytes).

Click on images to see enlarged views (172,493 and 155,266 bytes).

Today Nikon USA is the official distributor in the Americas of most consumer and professional Nikon products. However, Nikon USA does not import some of the rarer or specialized, limited demand products made by Nikon. In support of the markets served by Company Seven we have made arrangements to import directly from Japan a number of specialized products. At times and in support of some products we bring in from Nikon Japan we will order accessories from Nikon USA. As such Company Seven's staff will be your primary source of information regarding technical information about these products, current prices, estimated delivery dates and the status of your order.

We maintain a technically competent staff, each with at least 15 to 20 years or more experience using such equipment in addition to any formal technical and or engineering training. We have an uncommonly good theoretical and practical understanding of these Nikon products, their design and applications. It will become obvious as you browse our Internet site articles that our staff takes more interest in helping to make our customers well informed, and successful than most retailers.

In addition, we are proud to show Nikon products in our fascinating showroom. Company Seven remains one of the very few businesses in the optics community that maintains a showroom displaying a representative selection of the better telescopes, special optics, and accessories. We invite you to either visit our showroom or contact us. This way you can obtain prompt and competent concise assistance which will address your particular needs and concerns.

Contents Copyright 1994-2017 Company Seven - All Rights Reserved